Tues June 24 2008

I received the following email yesterday, and thought it might be on

interest to you all. You might remember the column it refers to as the

one in which I compared parts prices in Sk and North Dakota. I have

removed the editor's name from the email. Suffice it to say it came from

very close to home. The implement dealer I think is behind this has been

a great fan of the Western Cdn Wheat Growers so it was likely a good

opportunity to knock me off entirely. So much for the freedom of the

press and free enterprise to boot. I don't really blame the editor. They

have 2 small papers and advertising from the dealership is constant and

likely quite important. However, it does give a window into how the

world runs. Notice that they didn't claim what I said was wrong....

Cheers,

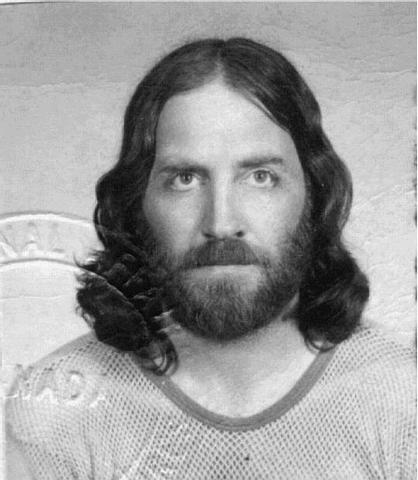

Paul

Paul

I am sorry to inform you that we are unable to run your column any

longer.

As you probably know the Column that you wrote about the implement

dealers

has caused quite an uproar and they are no longer advertising in our

paper.

They said they may continue to run if we remove your column completely,

so

regrettably we have to discontinue your column.

Please send your final bill and we will get you paid up.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

Monday, June 23, 2008

Conservative's CWB Strategy Loses in Court, Again

Column # 675 23/06/08

Chalk up another loss for Stephen Harper's government at the hands of

the Canadian Constitution. Two years ago then Agriculture Minister Chuck

Strahl slapped a gag order on the Canadian Wheat Board, prohibiting it

from doing anything to defend itself against attacks by the government

or the small anti-CWB groups that have sole access to the Minister's

ear. The CWB appealed this order to the federal court of Canada and the

ruling finally came down at the end of last week. Once again, as has

happened twice before, the Harper government was judged to have broken

the laws of the country in regard to the CWB.

Defenders of the gag order maintained it merely prevented the CWB from

spending farmers' money on propaganda. The federal court judge saw it

otherwise, saying, "It is entirely clear, therefore, that the directive

is motivated principally to silencing the Wheat Board in respect of any

promotion of a 'single desk' policy that it might do."

In fact, the gag order even prevented the Board from putting on its

website independent academic studies conducted at the University of

Saskatchewan and other such institutions. In this regard, the

government's strategy, as revealed in recent court documents seems to

have worked. Support for the CWB edged downward slightly in the recent

poll the Board conducted. As the independent pollster commented, if you

allow one side to speak and gag the other, the side able to put out its

message will gain support.

The CWB has now taken the federal government to court over four issues.

It has won three of them. The fourth was also ruled on last week. It was

the appeal of the government order requiring the CWB to pay Greg Arason

the paltry sum of $30,000 per month when the government fired Adrian

Measner and imposed Arason on the CWB as CEO.

Legally, the government could do that, since the CWB Act allows it to

appoint the CEO. However, the act also says that the directors set the

salary for the CEO. Harper's government refused to allow the CWB to do

this. The Board appealed, with the judge ruling that the case was now

moot. This means, essentially, that it is irrelevant, because Arason is

no longer the CEO, having taken his pitiful allowance and retired to

Florida.

Here again the government's strategy seems to have worked. The court

system moved so slowly that Arason did his appointed tenure, and his

damage as CEO, and got out while the getting was good, long before the

court caught up with his political masters. Had the court acted in a

timely manner, the government might not have been able to impose its

will on the directors whom farmers elected to run the CWB. The positive

aspect of the court decision is that it reaffirmed strongly that running

the CWB is the job of the directors, not the government.

Given the outcome of the three cases the courts did rule on, all in the

CWB's favor, you have to think the government has some pretty lousy

lawyers working for it if they keep advising courses of action that are

illegal. Not true, I suspect. The government's lawyers likely knew the

actions the government undertook were illegal, but the government went

ahead, knowing that it would accomplish some of its goals anyway. As I

said earlier, it did seem to improve its position in the battle for

public opinion, even if it ultimately lost the war at the courts. Same

for the firing of Measner and appointment of Arason. Among other things,

Arason fired Deanna Allen, as the anti-CWB groups had demanded, and got

his golden handshake.

It's a pretty cynical way for a government to act, but the government

appears to have gotten away with it to a great extent. While these

actions were condemned by some major farm groups, like Keystone

Agriculture Producers, the National Farmers Union and the Canadian

Federation of Agriculture, others were less vocal. APAS and SARM, the

farm groups in Saskatchewan that claim to have the broadest

constituencies, were silent on the government's illegal actions. Nor

should you expect much reaction now. SARM has effectively dropped out of

farm policy, while APAS is too busy firing its policy people to look up

from the vantage point it has between its legs. The APAS executive is

unlikely to criticize anything Conservative, no matter how undemocratic.

What's next on Harper's agenda for the CWB? Expect it to come in the

form of attempting to Gerry-mander the upcoming CWB director elections.

Harper's response to the court ruling was to maintain he would break the

CWB's single desk, no matter what, threatening to "walk over" anyone who

stands in his way. For now, however, the courts have said that even

Harper's government can't walk over the Canadian Constitution.

(c) Paul Beingessner

Chalk up another loss for Stephen Harper's government at the hands of

the Canadian Constitution. Two years ago then Agriculture Minister Chuck

Strahl slapped a gag order on the Canadian Wheat Board, prohibiting it

from doing anything to defend itself against attacks by the government

or the small anti-CWB groups that have sole access to the Minister's

ear. The CWB appealed this order to the federal court of Canada and the

ruling finally came down at the end of last week. Once again, as has

happened twice before, the Harper government was judged to have broken

the laws of the country in regard to the CWB.

Defenders of the gag order maintained it merely prevented the CWB from

spending farmers' money on propaganda. The federal court judge saw it

otherwise, saying, "It is entirely clear, therefore, that the directive

is motivated principally to silencing the Wheat Board in respect of any

promotion of a 'single desk' policy that it might do."

In fact, the gag order even prevented the Board from putting on its

website independent academic studies conducted at the University of

Saskatchewan and other such institutions. In this regard, the

government's strategy, as revealed in recent court documents seems to

have worked. Support for the CWB edged downward slightly in the recent

poll the Board conducted. As the independent pollster commented, if you

allow one side to speak and gag the other, the side able to put out its

message will gain support.

The CWB has now taken the federal government to court over four issues.

It has won three of them. The fourth was also ruled on last week. It was

the appeal of the government order requiring the CWB to pay Greg Arason

the paltry sum of $30,000 per month when the government fired Adrian

Measner and imposed Arason on the CWB as CEO.

Legally, the government could do that, since the CWB Act allows it to

appoint the CEO. However, the act also says that the directors set the

salary for the CEO. Harper's government refused to allow the CWB to do

this. The Board appealed, with the judge ruling that the case was now

moot. This means, essentially, that it is irrelevant, because Arason is

no longer the CEO, having taken his pitiful allowance and retired to

Florida.

Here again the government's strategy seems to have worked. The court

system moved so slowly that Arason did his appointed tenure, and his

damage as CEO, and got out while the getting was good, long before the

court caught up with his political masters. Had the court acted in a

timely manner, the government might not have been able to impose its

will on the directors whom farmers elected to run the CWB. The positive

aspect of the court decision is that it reaffirmed strongly that running

the CWB is the job of the directors, not the government.

Given the outcome of the three cases the courts did rule on, all in the

CWB's favor, you have to think the government has some pretty lousy

lawyers working for it if they keep advising courses of action that are

illegal. Not true, I suspect. The government's lawyers likely knew the

actions the government undertook were illegal, but the government went

ahead, knowing that it would accomplish some of its goals anyway. As I

said earlier, it did seem to improve its position in the battle for

public opinion, even if it ultimately lost the war at the courts. Same

for the firing of Measner and appointment of Arason. Among other things,

Arason fired Deanna Allen, as the anti-CWB groups had demanded, and got

his golden handshake.

It's a pretty cynical way for a government to act, but the government

appears to have gotten away with it to a great extent. While these

actions were condemned by some major farm groups, like Keystone

Agriculture Producers, the National Farmers Union and the Canadian

Federation of Agriculture, others were less vocal. APAS and SARM, the

farm groups in Saskatchewan that claim to have the broadest

constituencies, were silent on the government's illegal actions. Nor

should you expect much reaction now. SARM has effectively dropped out of

farm policy, while APAS is too busy firing its policy people to look up

from the vantage point it has between its legs. The APAS executive is

unlikely to criticize anything Conservative, no matter how undemocratic.

What's next on Harper's agenda for the CWB? Expect it to come in the

form of attempting to Gerry-mander the upcoming CWB director elections.

Harper's response to the court ruling was to maintain he would break the

CWB's single desk, no matter what, threatening to "walk over" anyone who

stands in his way. For now, however, the courts have said that even

Harper's government can't walk over the Canadian Constitution.

(c) Paul Beingessner

Monday, June 16, 2008

Farmers Pay the Piper, Someone Else Calls the Tune

Column # 674 16/06/08

Just an opinion here, but if ever there was an issue that farmers have

messed up, it has to be the issue of control over new plant varieties.

There was a time when development of new crop varieties was largely done

by universities and federal and provincial government research centres.

Varieties were distributed to grower organizations and royalties were

collected from them based on seed sales. The system worked, according to

plant breeders I've talked to.

It worked that is, for farmers and plant breeders. However, chemical

companies began to see the possibility of integrating sales of chemicals

with seed sales. If they could just breed plants that required their

chemicals, what a wonderful world it would be. Even better if they could

make money off the sale of both the chemical and the seed. The cherry on

top would be if farmers had to buy the seed every year.

Of course, all this wasn't possible within the legislative framework

that existed twenty years ago. The Plant Breeders Rights Act changed all

that. It continued to allow farmers to save seed for their own use, but

disallowed them from selling it, or giving it away to anyone. It allowed

companies, in effect, to control the release of varieties. Largely,

these were not varieties any company had developed, since most research

continued to be done with public and farmer money. Companies simply bid

for the right to "own" a variety. The trade-off was that money from the

purchasing of the rights to a variety went back to fund further

research. The problem was that farmers were now also contributing to the

fattening of the profits of seed companies.

Plant breeders rights were expanded further when governments, like

Canada, decided they would allow for the patenting of life forms. This

had been a no-no for as long as patents existed. The result, besides all

the bio-piracy that ensued, was to see companies patenting genes from

plants. This gave them the right to control not just the seed the farmer

planted, but also the seed he grew, so that companies are now able to

force farmers to follow their every dictum if they want to grow certain

varieties. An example in Canada is the requirement imposed by several

rights holders that you sell your production through certain channels,

and not to anyone else.

Farmers have always played a part in funding plant breeding. This has

been done through royalties they pay on certified seed and through

check-offs on the sale of crops. An example is the wheat and barley

check-off administered by the Canadian Wheat Board. In fact, if you get

right down to it, farmers or taxpayers pay for all plant breeding.

Private companies that do some breeding simply use money derived from

seed sales to farmers. A lot more of that money goes to other things.

One plant breeder working for a multinational company complained to me

that he would be ecstatic if his research budget was even a small

fraction of the money the company spent on advertising.

The trouble with plant breeding today is that research done by the

public sector is increasingly being turned over to the private sector to

allow it to make greater profits from farmers. The public good seems

forgotten in all this. And we are barely seeing the tip of the iceberg.

Farmers are still growing many varieties that were registered under the

old system and before the craze for proprietary ownership took over.

Immediately following the implementation of Plant Breeders Rights, few

varieties were covered. Now, virtually every new variety that comes out

is protected by PBRs. As well, chemical seed and grain companies like

Viterra and Farm Pure Seeds are increasingly tying up farmers with

contractual arrangements which don't even allow them to save their own

seed of publicly developed varieties.

And ultimately, farmers are to blame for this. They could have a great

deal of control over the registration process, since they contribute

huge amounts to plant breeding, and they have input through

organizations like the Western Grains Research Foundation, but they've

allowed a system to develop that serves the best interests of seed

companies and seed growers. And don't think it's done yet. Seed growers

have been lobbying for such measures as requiring the use of pedigreed

seed if you want to participate in crop insurance programs.

Transnationals like Monsanto want to collect royalties when the farmer

sells his crop to be sure they get every pound of flesh available.

A recent report done for the federal government might have some

implications for all this. The report on "Inter-Sectoral Partnerships

for Non-Regulatory Federal Laboratories" is suggesting a new research

center be developed. It would be called the Canadian Cereal Research and

Innovation Laboratory (CCRIL) and would bring together many of the

agencies involved in cereal research. While this may be as simple as

housing different agencies under a single roof, the implications may

reach further. The report strongly suggested that the best model for

research was one that integrated federal government research agencies

with provincial universities and the private sector under a management

scheme that was independent of the federal government.

Given the bent of the current federal government, this sounds an awful

lot like privatisation to me. However, the proponents of the CCRIL are

mostly public sector. They include the Canadian Grain Commission, the

Canadian International Grains Institute, the University of Manitoba and

the Canadian Wheat Board.

Perhaps the notion of a new research center opens an opportunity for

farmers to re-examine the registration system and who benefits from it.

It really is time the guy paying the piper started to call the tune.

(c) Paul Beingessner

Just an opinion here, but if ever there was an issue that farmers have

messed up, it has to be the issue of control over new plant varieties.

There was a time when development of new crop varieties was largely done

by universities and federal and provincial government research centres.

Varieties were distributed to grower organizations and royalties were

collected from them based on seed sales. The system worked, according to

plant breeders I've talked to.

It worked that is, for farmers and plant breeders. However, chemical

companies began to see the possibility of integrating sales of chemicals

with seed sales. If they could just breed plants that required their

chemicals, what a wonderful world it would be. Even better if they could

make money off the sale of both the chemical and the seed. The cherry on

top would be if farmers had to buy the seed every year.

Of course, all this wasn't possible within the legislative framework

that existed twenty years ago. The Plant Breeders Rights Act changed all

that. It continued to allow farmers to save seed for their own use, but

disallowed them from selling it, or giving it away to anyone. It allowed

companies, in effect, to control the release of varieties. Largely,

these were not varieties any company had developed, since most research

continued to be done with public and farmer money. Companies simply bid

for the right to "own" a variety. The trade-off was that money from the

purchasing of the rights to a variety went back to fund further

research. The problem was that farmers were now also contributing to the

fattening of the profits of seed companies.

Plant breeders rights were expanded further when governments, like

Canada, decided they would allow for the patenting of life forms. This

had been a no-no for as long as patents existed. The result, besides all

the bio-piracy that ensued, was to see companies patenting genes from

plants. This gave them the right to control not just the seed the farmer

planted, but also the seed he grew, so that companies are now able to

force farmers to follow their every dictum if they want to grow certain

varieties. An example in Canada is the requirement imposed by several

rights holders that you sell your production through certain channels,

and not to anyone else.

Farmers have always played a part in funding plant breeding. This has

been done through royalties they pay on certified seed and through

check-offs on the sale of crops. An example is the wheat and barley

check-off administered by the Canadian Wheat Board. In fact, if you get

right down to it, farmers or taxpayers pay for all plant breeding.

Private companies that do some breeding simply use money derived from

seed sales to farmers. A lot more of that money goes to other things.

One plant breeder working for a multinational company complained to me

that he would be ecstatic if his research budget was even a small

fraction of the money the company spent on advertising.

The trouble with plant breeding today is that research done by the

public sector is increasingly being turned over to the private sector to

allow it to make greater profits from farmers. The public good seems

forgotten in all this. And we are barely seeing the tip of the iceberg.

Farmers are still growing many varieties that were registered under the

old system and before the craze for proprietary ownership took over.

Immediately following the implementation of Plant Breeders Rights, few

varieties were covered. Now, virtually every new variety that comes out

is protected by PBRs. As well, chemical seed and grain companies like

Viterra and Farm Pure Seeds are increasingly tying up farmers with

contractual arrangements which don't even allow them to save their own

seed of publicly developed varieties.

And ultimately, farmers are to blame for this. They could have a great

deal of control over the registration process, since they contribute

huge amounts to plant breeding, and they have input through

organizations like the Western Grains Research Foundation, but they've

allowed a system to develop that serves the best interests of seed

companies and seed growers. And don't think it's done yet. Seed growers

have been lobbying for such measures as requiring the use of pedigreed

seed if you want to participate in crop insurance programs.

Transnationals like Monsanto want to collect royalties when the farmer

sells his crop to be sure they get every pound of flesh available.

A recent report done for the federal government might have some

implications for all this. The report on "Inter-Sectoral Partnerships

for Non-Regulatory Federal Laboratories" is suggesting a new research

center be developed. It would be called the Canadian Cereal Research and

Innovation Laboratory (CCRIL) and would bring together many of the

agencies involved in cereal research. While this may be as simple as

housing different agencies under a single roof, the implications may

reach further. The report strongly suggested that the best model for

research was one that integrated federal government research agencies

with provincial universities and the private sector under a management

scheme that was independent of the federal government.

Given the bent of the current federal government, this sounds an awful

lot like privatisation to me. However, the proponents of the CCRIL are

mostly public sector. They include the Canadian Grain Commission, the

Canadian International Grains Institute, the University of Manitoba and

the Canadian Wheat Board.

Perhaps the notion of a new research center opens an opportunity for

farmers to re-examine the registration system and who benefits from it.

It really is time the guy paying the piper started to call the tune.

(c) Paul Beingessner

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

American Farmers Get Break on Parts

Column #673 American Farmers Get Break on Parts 09/06/08

As we shared the loading of a producer car last week, my cousin shook

his head in amazement. "You know, half of this car is worth about

$20,000." It put a bit of a glow on an otherwise cool day to realize

that he was right. High protein number one durum is at a premium price

this year and dropping it into a producer car put the icing on the cake.

I grabbed the mail on the way home when the job was done. I should have

waited a while to open it, what with the glow still lingering. The fuel

bill that came in that day's mail wiped off my smile and caused a

reassessment of my good fortune. Call it sticker shock, I guess, but the

bill for diesel fuel that accompanied this year's seeding brought a

different kind of shine to my face. That last fill cost me $1.15 per

litre for diesel, while gasoline carried a price of $1.21 a litre.

It prompted me to dig out last year's spring fuel bill. Back then, durum

may have been a fraction of today's price, but so was fuel, with diesel

at 72.9 cents a litre and gasoline at $106.9. Probably few farmers are

assuming the price has peaked either. If gasoline might hit $1.50 by

July, we can expect diesel to be close behind.

The increase in fuel costs has prompted many urban motorists to blow the

dust off the bicycle and has even started some debating the merits of

the city bus. Farmers don't get much use from those two items, burdened

down as we are by fuel tanks and tools and large implements, but farmers

too are looking for ways to cut fuel consumption.

When it comes to buying parts however, they may want to consider the

benefits of burning a bit more fuel, at least if they're within driving

distance of the U.S. Equipment parts, of every type and for every brand,

appear to be much lower priced in our neighbour to the south. While I

might have been able to understand this when the Canadian dollar was at

70 cents U.S., it becomes a bit more difficult to swallow when the

dollar is at par, or higher.

How big are the differences? I did some comparisons between prices in

Saskatchewan and in Minot, North Dakota, about 240 miles south east of

my farm. The differences were strikingly consistent, from John Deere to

New Holland to CIH and Versatile. Parts at Minot were generally about 24

percent lower than the same part in Saskatchewan. This held not only

from one manufacturer to another, but from tractors to haybines to

balers, and from small items to big.

A tachometer for an ageing 3020 John Deere tractor will set you back

$283 in Saskatchewan but only cost $230 in Minot. A hydraulic pump for a

somewhat newer 4430 costs $2,171 in Regina but you could save $421 by

taking that trip to North Dakota. A remanufactured engine for a 8460

John Deere tractor finds a price of $12,900 in Minot, but somehow is

worth $15,983 when the currency and location are Canadian.

While car buyers have complained bitterly about the difference in auto

prices between here and the U.S., to some positive effect, farmers have

been rather quiet about the prices they have to pay for parts. One

fellow at a parts counter assured me that the price difference had

indeed declined recently, but that only served to make me more annoyed

as I contemplated the rip-off I have apparently been enduring for some

time. He also said that the price spread on new equipment was hurting

their business.

Not every farmer in the west is close enough to a major U.S. city to run

down for every parts order. However, the farmer who needs a big ticket

repair item, or who compiles a list of smaller ones might find a

handsome reward in taking a trip south. If enough farmers do it,

Canadian dealers will have to find ways to pressure their parent

companies to stop treating Canadian farmers like a huge cash cow. If the

rise in the Canadian dollar has driven down the price of many of the

products we sell, we should at least be able to get some small benefit

from it.

(c) Paul Beingessner

As we shared the loading of a producer car last week, my cousin shook

his head in amazement. "You know, half of this car is worth about

$20,000." It put a bit of a glow on an otherwise cool day to realize

that he was right. High protein number one durum is at a premium price

this year and dropping it into a producer car put the icing on the cake.

I grabbed the mail on the way home when the job was done. I should have

waited a while to open it, what with the glow still lingering. The fuel

bill that came in that day's mail wiped off my smile and caused a

reassessment of my good fortune. Call it sticker shock, I guess, but the

bill for diesel fuel that accompanied this year's seeding brought a

different kind of shine to my face. That last fill cost me $1.15 per

litre for diesel, while gasoline carried a price of $1.21 a litre.

It prompted me to dig out last year's spring fuel bill. Back then, durum

may have been a fraction of today's price, but so was fuel, with diesel

at 72.9 cents a litre and gasoline at $106.9. Probably few farmers are

assuming the price has peaked either. If gasoline might hit $1.50 by

July, we can expect diesel to be close behind.

The increase in fuel costs has prompted many urban motorists to blow the

dust off the bicycle and has even started some debating the merits of

the city bus. Farmers don't get much use from those two items, burdened

down as we are by fuel tanks and tools and large implements, but farmers

too are looking for ways to cut fuel consumption.

When it comes to buying parts however, they may want to consider the

benefits of burning a bit more fuel, at least if they're within driving

distance of the U.S. Equipment parts, of every type and for every brand,

appear to be much lower priced in our neighbour to the south. While I

might have been able to understand this when the Canadian dollar was at

70 cents U.S., it becomes a bit more difficult to swallow when the

dollar is at par, or higher.

How big are the differences? I did some comparisons between prices in

Saskatchewan and in Minot, North Dakota, about 240 miles south east of

my farm. The differences were strikingly consistent, from John Deere to

New Holland to CIH and Versatile. Parts at Minot were generally about 24

percent lower than the same part in Saskatchewan. This held not only

from one manufacturer to another, but from tractors to haybines to

balers, and from small items to big.

A tachometer for an ageing 3020 John Deere tractor will set you back

$283 in Saskatchewan but only cost $230 in Minot. A hydraulic pump for a

somewhat newer 4430 costs $2,171 in Regina but you could save $421 by

taking that trip to North Dakota. A remanufactured engine for a 8460

John Deere tractor finds a price of $12,900 in Minot, but somehow is

worth $15,983 when the currency and location are Canadian.

While car buyers have complained bitterly about the difference in auto

prices between here and the U.S., to some positive effect, farmers have

been rather quiet about the prices they have to pay for parts. One

fellow at a parts counter assured me that the price difference had

indeed declined recently, but that only served to make me more annoyed

as I contemplated the rip-off I have apparently been enduring for some

time. He also said that the price spread on new equipment was hurting

their business.

Not every farmer in the west is close enough to a major U.S. city to run

down for every parts order. However, the farmer who needs a big ticket

repair item, or who compiles a list of smaller ones might find a

handsome reward in taking a trip south. If enough farmers do it,

Canadian dealers will have to find ways to pressure their parent

companies to stop treating Canadian farmers like a huge cash cow. If the

rise in the Canadian dollar has driven down the price of many of the

products we sell, we should at least be able to get some small benefit

from it.

(c) Paul Beingessner

Bemoaning the State of the Beef Industry

Column # 672 Bemoaning the State of the Beef Industry 02/06/08

From time to time, folks commenting on the state of the beef industry

in Canada will bemoan the fact that, post-BSE, we are still heavily

dependent on the U.S. as a market for our cattle. It seems, in fact,

that we have ramped up cattle exports to our southern neighbour to the

point where they now exceed the numbers we were shipping before Mad Cow

reared its ugly head.

While the moaners usually don't blame any specific group for this

short-sightedness, preferring instead to use the meaningless "we", it is

clear farmers are seen as one of the guilty parties. And they should be,

but not in the way you might think. Farmers in many parts of Canada did

their best to generate other ways of marketing their beef. They

supported a number of new beef slaughtering initiatives, most of them

focused on developing niche markets for some specialty type of beef, be

it grass-fed, natural, or cull cow. This is what they did, but

unfortunately the results have been less than sterling. Most of the

plans came to nothing, and most of those that got beyond the planning

stage didn't last long after opening.

These two things, the failure of local initiatives and the renewed focus

on American markets were predicted by many and were completely logical.

The local initiatives were doomed from the start. Most relied on overly

optimistic scenarios generated by consultants who knew that a consultant

with negative reports will have a relatively short career. They were

likely the same consulting firms that a decade ago were recommending a

pulse processing plant at every siding. Prior to that, they made their

living by recommending hog barns ad infinitum.

In truth, niche markets for specially raised beef have always been quite

limited. Even discriminating consumers will only pay a small premium for

their vices. And the cull cow and bull operations have to compete with a

product that oozes from the large packers in unbelievable quantities.

Competing head on with Cargill is not a recipe for success.

That Canadian cattle are again gravitating to the U.S. in huge numbers

is scant surprise. Cattle will go where the cheapest feed and the lowest

cost labour are found. American corn, biofuel demand notwithstanding, is

still a cheaper feed than nearly anything else. And Alberta's packing

plants, the largest in Canada, are competing for labour with a booming

oil sector that pays real wages.

That my friends is the free market. In today's environment of global,

monopoly capitalism, farmers can have little impact on the direction

that market moves. There certainly never was any opportunity for farmers

to somehow influence the development of new markets for Canadian beef.

Farmers are not players in the packing industry today, except in Quebec.

That business is held tightly in the grip of about four companies. They

are the ones who develop markets, and they do so in whatever way suits

their needs, not the needs of Canadian farmers and ranchers. Nor is

their much point blaming the big packers. They are just doing what they

are able to do in an environment where there are few rules.

In light of this, why do I say that farmers are to blame? It is because

farmers typically see only three possible responses to a melt-down like

that caused by BSE. They can fold and leave the industry, they can

decide to tough it out and hope for better times, or they can remain

peripherally in the industry while finding other ways to make a living.

The other possibility, that of working together to find the root causes

of the industry's troubles and exploring alternative ways of organizing

the industry, doesn't seem to be on the radar for farmers.

Now, as feedlots close in beef country we are told to find a new way of

raising our cattle. Feed grains are too expensive so cattle must stay on

grass longer and face shorter periods in a feedlot. This is not a bad

thing. It may in fact be a good thing from an environmental and animal

welfare point of view. But the reality is that farmers are told to keep

their calves six to 12 months longer, and then sell them for the same

price they were getting for six-month-old calves in 2002. How does that

work?

Meanwhile, beef industry observers are telling us that those who hang on

are going to be the winners when the price eventually goes up. Sounds

like some consultants I know...

(c) Paul Beingessner

From time to time, folks commenting on the state of the beef industry

in Canada will bemoan the fact that, post-BSE, we are still heavily

dependent on the U.S. as a market for our cattle. It seems, in fact,

that we have ramped up cattle exports to our southern neighbour to the

point where they now exceed the numbers we were shipping before Mad Cow

reared its ugly head.

While the moaners usually don't blame any specific group for this

short-sightedness, preferring instead to use the meaningless "we", it is

clear farmers are seen as one of the guilty parties. And they should be,

but not in the way you might think. Farmers in many parts of Canada did

their best to generate other ways of marketing their beef. They

supported a number of new beef slaughtering initiatives, most of them

focused on developing niche markets for some specialty type of beef, be

it grass-fed, natural, or cull cow. This is what they did, but

unfortunately the results have been less than sterling. Most of the

plans came to nothing, and most of those that got beyond the planning

stage didn't last long after opening.

These two things, the failure of local initiatives and the renewed focus

on American markets were predicted by many and were completely logical.

The local initiatives were doomed from the start. Most relied on overly

optimistic scenarios generated by consultants who knew that a consultant

with negative reports will have a relatively short career. They were

likely the same consulting firms that a decade ago were recommending a

pulse processing plant at every siding. Prior to that, they made their

living by recommending hog barns ad infinitum.

In truth, niche markets for specially raised beef have always been quite

limited. Even discriminating consumers will only pay a small premium for

their vices. And the cull cow and bull operations have to compete with a

product that oozes from the large packers in unbelievable quantities.

Competing head on with Cargill is not a recipe for success.

That Canadian cattle are again gravitating to the U.S. in huge numbers

is scant surprise. Cattle will go where the cheapest feed and the lowest

cost labour are found. American corn, biofuel demand notwithstanding, is

still a cheaper feed than nearly anything else. And Alberta's packing

plants, the largest in Canada, are competing for labour with a booming

oil sector that pays real wages.

That my friends is the free market. In today's environment of global,

monopoly capitalism, farmers can have little impact on the direction

that market moves. There certainly never was any opportunity for farmers

to somehow influence the development of new markets for Canadian beef.

Farmers are not players in the packing industry today, except in Quebec.

That business is held tightly in the grip of about four companies. They

are the ones who develop markets, and they do so in whatever way suits

their needs, not the needs of Canadian farmers and ranchers. Nor is

their much point blaming the big packers. They are just doing what they

are able to do in an environment where there are few rules.

In light of this, why do I say that farmers are to blame? It is because

farmers typically see only three possible responses to a melt-down like

that caused by BSE. They can fold and leave the industry, they can

decide to tough it out and hope for better times, or they can remain

peripherally in the industry while finding other ways to make a living.

The other possibility, that of working together to find the root causes

of the industry's troubles and exploring alternative ways of organizing

the industry, doesn't seem to be on the radar for farmers.

Now, as feedlots close in beef country we are told to find a new way of

raising our cattle. Feed grains are too expensive so cattle must stay on

grass longer and face shorter periods in a feedlot. This is not a bad

thing. It may in fact be a good thing from an environmental and animal

welfare point of view. But the reality is that farmers are told to keep

their calves six to 12 months longer, and then sell them for the same

price they were getting for six-month-old calves in 2002. How does that

work?

Meanwhile, beef industry observers are telling us that those who hang on

are going to be the winners when the price eventually goes up. Sounds

like some consultants I know...

(c) Paul Beingessner

Joy in Mudville

Column # 671 Joy in Mudville 26/05/08

The drought affecting farmers in many parts of the prairie provinces is

starting to take on frightening proportions. That there is a drought is

not news for farmers south of the Trans Canada Highway, who have endured

several years of it, but even these weather-beaten folk might be

surprised to hear how far afield that drought has travelled. A recent

listing of rainfall in Saskatchewan from April 1 onward showed that the

three driest points in the province were Estevan (south east), Val Marie

(south west) and Prince Albert (north central). While a few pockets have

received adequate rain, there is a lot of dry land in between.

Travelling west on the Trans Canada last week, I saw Reed Lake, a saline

lake that butts against the highway east of Swift Current. In the spring

it is usually teeming with shorebirds and waterfowl. It was a first for

me to see the lake entirely dry, its salt-encrusted shores now extending

south to the horizon.

Closer to home, the coulees and creek that provide surface water and

shallow wells for many farmers in this area failed to run at all this

spring. It is only the second time in my life I can recall this

happening. Sloughs in the Missouri Couteau west and south of our farm,

which usually produce ducks in the spring and hay in late summer, are

dry. Pastures have hardly grown an inch or two, and farmers are

struggling to find enough grass to carry their livestock while they

await the rain. We have had no really meaningful rain since last May.

The prospect of poor crops in one of the best years for price in recent

memory might make a grain farmer glum, especially considering the value

of inputs that went into the ground with that seed. Bit it is livestock

producers who have a great deal to sweat about immediately. Most have

consumed any reserves of hay they may have had, and pastures were

overgrazed in many areas last year. Hay grows in May and June, and May

has been abysmally dry. There are about four weeks left to make a hay

crop, and it will take a lot of rain.

So it's been tough around here. I've tried to hold the cattle off their

summer pasture, as the grass is very short, and won't last long, but I

figure the spring pasture will hold them for only a few more days.

Fretting and staring at the sky have become near-constant occupations on

the farm.

Fortunately, things get put into perspective now and then, and a phone

call from a nephew did that for me today. He told a story of a rancher

in the Climax area in southwest Saskatchewan who had purchased a large

quantity of hay from my nephew's neighbour last year. The hay had to be

trucked several hundred miles. In the winter, the rancher bought the

rest of the hay. He phoned the fellow who sold the hay recently to ask

what things looked like for this year. The rancher had fed all the hay,

his pastures were bare from lack of rain and his dugouts had gone

completely dry. He had broken up some of his hay and pastureland in an

attempt to starve the flourishing gopher populations. He was now looking

for a place to pasture his cows in the northern grainbelt. No doubt his

neighbours are in the same position.

Bad as our own situation is, that story made me stop to count my

blessings. If the drought continues, we may be in that rancher's

position soon, but we aren't quite there yet.

This weekend, a bit of rain fell across much of the southern prairies.

There was great joy in mudville at the notion that crops in dry soil now

at least have a chance to germinate. It was only a half-inch, but at

least we know now that it can still rain in this country. We were

starting to doubt that.

(c) Paul Beingessner

The drought affecting farmers in many parts of the prairie provinces is

starting to take on frightening proportions. That there is a drought is

not news for farmers south of the Trans Canada Highway, who have endured

several years of it, but even these weather-beaten folk might be

surprised to hear how far afield that drought has travelled. A recent

listing of rainfall in Saskatchewan from April 1 onward showed that the

three driest points in the province were Estevan (south east), Val Marie

(south west) and Prince Albert (north central). While a few pockets have

received adequate rain, there is a lot of dry land in between.

Travelling west on the Trans Canada last week, I saw Reed Lake, a saline

lake that butts against the highway east of Swift Current. In the spring

it is usually teeming with shorebirds and waterfowl. It was a first for

me to see the lake entirely dry, its salt-encrusted shores now extending

south to the horizon.

Closer to home, the coulees and creek that provide surface water and

shallow wells for many farmers in this area failed to run at all this

spring. It is only the second time in my life I can recall this

happening. Sloughs in the Missouri Couteau west and south of our farm,

which usually produce ducks in the spring and hay in late summer, are

dry. Pastures have hardly grown an inch or two, and farmers are

struggling to find enough grass to carry their livestock while they

await the rain. We have had no really meaningful rain since last May.

The prospect of poor crops in one of the best years for price in recent

memory might make a grain farmer glum, especially considering the value

of inputs that went into the ground with that seed. Bit it is livestock

producers who have a great deal to sweat about immediately. Most have

consumed any reserves of hay they may have had, and pastures were

overgrazed in many areas last year. Hay grows in May and June, and May

has been abysmally dry. There are about four weeks left to make a hay

crop, and it will take a lot of rain.

So it's been tough around here. I've tried to hold the cattle off their

summer pasture, as the grass is very short, and won't last long, but I

figure the spring pasture will hold them for only a few more days.

Fretting and staring at the sky have become near-constant occupations on

the farm.

Fortunately, things get put into perspective now and then, and a phone

call from a nephew did that for me today. He told a story of a rancher

in the Climax area in southwest Saskatchewan who had purchased a large

quantity of hay from my nephew's neighbour last year. The hay had to be

trucked several hundred miles. In the winter, the rancher bought the

rest of the hay. He phoned the fellow who sold the hay recently to ask

what things looked like for this year. The rancher had fed all the hay,

his pastures were bare from lack of rain and his dugouts had gone

completely dry. He had broken up some of his hay and pastureland in an

attempt to starve the flourishing gopher populations. He was now looking

for a place to pasture his cows in the northern grainbelt. No doubt his

neighbours are in the same position.

Bad as our own situation is, that story made me stop to count my

blessings. If the drought continues, we may be in that rancher's

position soon, but we aren't quite there yet.

This weekend, a bit of rain fell across much of the southern prairies.

There was great joy in mudville at the notion that crops in dry soil now

at least have a chance to germinate. It was only a half-inch, but at

least we know now that it can still rain in this country. We were

starting to doubt that.

(c) Paul Beingessner

When Mud Pies Are No Longer a Game

Column # 670 19/05/08

When I was a kid, my two older sisters were experts at making mud pies.

In fact, their expertise went far beyond the lowly mud pie. They made

mud cookies, mud cakes, mud vegetables and even mud mashed potatoes.

After careful shaping and drying in the sun, they looked good enough to

eat. Which we did, sort of. Part of getting into the game, and being

allowed to be there at all, was to play along with the fantasy,

pretending to nibble at the food, while exclaiming over the skill of the

cooks.

My sisters eventually went on to other things, like teaching and

nursing. But it is kind of comforting to know that, had they not been

successful at these occupations, they could have put the skills of

childhood to good use, even as adults. They could have, that is, if they

lived in Haiti. In Haiti, grown people make mud cookies. But, unlike my

younger siblings and me, eating them isn't a matter of pretending. The

cookies, made of a soft clay mixed with salt, water and shortening, are

the way impoverished Haitians stave off hunger pains when they can't

afford real food. It's a story that almost beggars belief.

Haiti is undoubtedly the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

Unlike many third world countries that have at least held their own,

Haiti's per capita GDP is far smaller than it was 30 years ago. Yet, the

country of eight million is home to a tiny elite, a few thousand

families that are tremendously wealthy, and control the Haitian economy.

This elite shops in Miami, sends its children to Europe to be educated,

and lives in a world completely unlike the 80 percent of Haitians who

live in grinding poverty.

Haiti's poverty is no accident however. It is partly due to years of

military dictatorships that were supported by the U.S., and partly due

to "structural adjustments" that the World Bank forced upon the country

as a precondition to receiving aid. The Bank's economic plan for Haiti

included privatizing key infrastructure and entrusting the delivery of

education, health, family planning, and water supply and sanitation to

private corporations. This was supposed to stimulate the Haitian economy

and bring investment into the country. Never mind that developed

countries generally wouldn't dream of turning these services over to

for-profit enterprises.

As part of this structural change, Haiti opened its border to imports of

food. The resulting flood of cheap food drove local farmers out of

business and reduced local food production. Once a rice exporter, Haiti

now relies on imports for over 80 percent of rice consumption. With food

prices rising around the world this year, imported food is no longer so

cheap. The $2 a day earned by someone lucky enough to have a job in

Haiti will buy only a couple cups of rice.

Canadian farmers are well aware of the benefits for us of trade

agreements that lower tariff barriers. We have spent years watching the

world trade talks, with their improbable promise of prosperity for all,

flounder over this issue. What we don't like to think about are the

effects trade liberalization might have on farmers in other countries.

The example of Haiti, the most "open" country in the region, is far from

unusual. With our superior technology and government subsidies, rich

countries can often insert their farm production into countries that

can't possibly compete. The result for the poor country's food

sovereignty and agriculture sector can be devastating.

Farmers in Canada have been an unhappy lot for decades. Current grain

prices portend potential for a change to their circumstances, but some

of the current upturn in prices is being bought at the expense of

farmers elsewhere. We should remember that when our politicians push

freer trade as the answer to our problems.

(c) Paul Beingessner

When I was a kid, my two older sisters were experts at making mud pies.

In fact, their expertise went far beyond the lowly mud pie. They made

mud cookies, mud cakes, mud vegetables and even mud mashed potatoes.

After careful shaping and drying in the sun, they looked good enough to

eat. Which we did, sort of. Part of getting into the game, and being

allowed to be there at all, was to play along with the fantasy,

pretending to nibble at the food, while exclaiming over the skill of the

cooks.

My sisters eventually went on to other things, like teaching and

nursing. But it is kind of comforting to know that, had they not been

successful at these occupations, they could have put the skills of

childhood to good use, even as adults. They could have, that is, if they

lived in Haiti. In Haiti, grown people make mud cookies. But, unlike my

younger siblings and me, eating them isn't a matter of pretending. The

cookies, made of a soft clay mixed with salt, water and shortening, are

the way impoverished Haitians stave off hunger pains when they can't

afford real food. It's a story that almost beggars belief.

Haiti is undoubtedly the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

Unlike many third world countries that have at least held their own,

Haiti's per capita GDP is far smaller than it was 30 years ago. Yet, the

country of eight million is home to a tiny elite, a few thousand

families that are tremendously wealthy, and control the Haitian economy.

This elite shops in Miami, sends its children to Europe to be educated,

and lives in a world completely unlike the 80 percent of Haitians who

live in grinding poverty.

Haiti's poverty is no accident however. It is partly due to years of

military dictatorships that were supported by the U.S., and partly due

to "structural adjustments" that the World Bank forced upon the country

as a precondition to receiving aid. The Bank's economic plan for Haiti

included privatizing key infrastructure and entrusting the delivery of

education, health, family planning, and water supply and sanitation to

private corporations. This was supposed to stimulate the Haitian economy

and bring investment into the country. Never mind that developed

countries generally wouldn't dream of turning these services over to

for-profit enterprises.

As part of this structural change, Haiti opened its border to imports of

food. The resulting flood of cheap food drove local farmers out of

business and reduced local food production. Once a rice exporter, Haiti

now relies on imports for over 80 percent of rice consumption. With food

prices rising around the world this year, imported food is no longer so

cheap. The $2 a day earned by someone lucky enough to have a job in

Haiti will buy only a couple cups of rice.

Canadian farmers are well aware of the benefits for us of trade

agreements that lower tariff barriers. We have spent years watching the

world trade talks, with their improbable promise of prosperity for all,

flounder over this issue. What we don't like to think about are the

effects trade liberalization might have on farmers in other countries.

The example of Haiti, the most "open" country in the region, is far from

unusual. With our superior technology and government subsidies, rich

countries can often insert their farm production into countries that

can't possibly compete. The result for the poor country's food

sovereignty and agriculture sector can be devastating.

Farmers in Canada have been an unhappy lot for decades. Current grain

prices portend potential for a change to their circumstances, but some

of the current upturn in prices is being bought at the expense of

farmers elsewhere. We should remember that when our politicians push

freer trade as the answer to our problems.

(c) Paul Beingessner

Viterra Takes a Page from Monsanto

Column # 669 12/05/08

While I don't expect to get dragged through the court system anytime

soon, I did get an inkling last week of how Percy Schmeiser must have

felt when he got that first letter from Monsanto. Mine came in the form

of a letter from Viterra, that amalgam of the once-farmer-owned prairie

grain companies. It began politely enough, thanking me for my business,

but soon turned ugly. Viterra, it seems, is about to become the Monsanto

of durum.

Monsanto, of course, is famous for suing farmers it believes have

infringed on its patent over the Roundup Ready gene. Percy Schmeiser is

likely the best known farmer to reap Monsanto's wrath, at least in

Canada, but he if far from the only one. Monsanto has hounded thousands

of farmers who it claims have grown Roundup Ready varieties of several

crops without paying the royalty the company demands. Some have ended up

in jail, many in financial ruin. Few had the nerve to defend themselves

to the extent that Percy did.

While Viterra doesn't own any genes related to durum, it does have

control over a couple of varieties - Navigator and Commander. Viterra

controls the production, sale and handling of these varieties. If you

want to grow them, you have to buy registered seed each year from

Viterra. You have to sell all your production to Viterra. And you have

to buy crop inputs, usually a certain dollar amount from Viterra. If

your crop is ruined by weather, you have to account to Viterra for how

you have disposed of the production.

Viterra, it appears, believes that farmers are not following the rules

with its durum varieties. The letter was to remind me of my "contractual

obligations under these Identity Preserved (IP) production contracts."

While Viterra is confident most farmers are following the terms of these

contracts, "regrettably, some are not". Then comes the threat, "Viterra

is considering all remedies, including legal action, to enforce these

rights and protect our IP programs."

Viterra, according to one source in the grain industry, is convinced a

great deal of Navigator durum is being grown outside its contracts, and

delivered to elevators as common durum. It is determined to get this

breach of its rules under control.

While the letter from Viterra made me feel real special, I suspect an

awful lot of farmers have received the same. Personally, I'm not sure

why I was on Viterra's list, since I haven't done any business of any

kind with the company for about a decade. Nor have I ever grown

Navigator or Commander durum.

So why do people grow these varieties, despite the downside of having to

buy new seed each year and being unable to access competitive buyers for

their production? Perhaps the biggest incentive is the guarantee that

the CWB will take all the Navigator that is produced under contract each

year. Navigator has one feature that is relatively unique among durums

at this time. It has a brighter yellow pigment in the seed and hence

produces brighter yellow pasta. There is a niche market for a small

amount of this durum, and Viterra limits production to this amount by

limiting the contracts it lets out.

Commander durum has less to commend it. Yields are fairly high relative

to other varieties, and like Navigator, Commander has stronger gluten

than other durums. However, Commander has the very undesirable habit of

accumulating cadmium in its seed. Cadmium is a toxic heavy metal that

has become a source of concern to consumers of durum. The CWB limits

contracts for Commander in certain parts of the prairies where cadmium

accumulation is especially problematic. Like Navigator, Commander also

limits what growers can do with their production. Many farmers don't see

the closed loop system as a desirable thing. There is some evidence to

indicate that farmers whose marketing options are restricted by

contracts receive lower trucking premiums and poorer grades when they

sell their grain.

Fortunately, those wanting to grow stronger gluten durum have an

alternative. Strongfield durum, developed by the same Agriculture Canada

scientists who developed Navigator and Commander, is a strong gluten

durum with superior milling qualities. It has better yields that

Navigator, and, with it being licensed to SeCan, farmers are able to

keep their own seed for replanting, and are not nearly so restricted in

marketing options.

The CWB has been anxious to get Strongfield into greater production (it

occupied 43% durum acres in Saskatchewan last year) in order to improve

the quality of the durum it sells. The CWB has also generally required

companies that want contracts for Strongfield to allow farmers to

replant their own seed.

Viterra's aggressive measures to protect its control over Navigator will

not sit well with many farmers. No one likes to think that the future of

grain production lies in closed loop contracts that limit a farmer's

access to both markets and farm supplies. The huge growth in Strongfield

acres indicates just that. Rumour has it that Viterra hasn't limited its

threats to farmers. Other grain companies have been told that they might

be held liable if they buy Navigator durum. At least one company

responded by saying that if Viterra allowed Navigator to contaminate its

elevators, Viterra would be held responsible.

(c) Paul Beingessner

While I don't expect to get dragged through the court system anytime

soon, I did get an inkling last week of how Percy Schmeiser must have

felt when he got that first letter from Monsanto. Mine came in the form

of a letter from Viterra, that amalgam of the once-farmer-owned prairie

grain companies. It began politely enough, thanking me for my business,

but soon turned ugly. Viterra, it seems, is about to become the Monsanto

of durum.

Monsanto, of course, is famous for suing farmers it believes have

infringed on its patent over the Roundup Ready gene. Percy Schmeiser is

likely the best known farmer to reap Monsanto's wrath, at least in

Canada, but he if far from the only one. Monsanto has hounded thousands

of farmers who it claims have grown Roundup Ready varieties of several

crops without paying the royalty the company demands. Some have ended up

in jail, many in financial ruin. Few had the nerve to defend themselves

to the extent that Percy did.

While Viterra doesn't own any genes related to durum, it does have

control over a couple of varieties - Navigator and Commander. Viterra

controls the production, sale and handling of these varieties. If you

want to grow them, you have to buy registered seed each year from

Viterra. You have to sell all your production to Viterra. And you have

to buy crop inputs, usually a certain dollar amount from Viterra. If

your crop is ruined by weather, you have to account to Viterra for how

you have disposed of the production.

Viterra, it appears, believes that farmers are not following the rules

with its durum varieties. The letter was to remind me of my "contractual

obligations under these Identity Preserved (IP) production contracts."

While Viterra is confident most farmers are following the terms of these

contracts, "regrettably, some are not". Then comes the threat, "Viterra

is considering all remedies, including legal action, to enforce these

rights and protect our IP programs."

Viterra, according to one source in the grain industry, is convinced a

great deal of Navigator durum is being grown outside its contracts, and

delivered to elevators as common durum. It is determined to get this

breach of its rules under control.

While the letter from Viterra made me feel real special, I suspect an

awful lot of farmers have received the same. Personally, I'm not sure

why I was on Viterra's list, since I haven't done any business of any

kind with the company for about a decade. Nor have I ever grown

Navigator or Commander durum.

So why do people grow these varieties, despite the downside of having to

buy new seed each year and being unable to access competitive buyers for

their production? Perhaps the biggest incentive is the guarantee that

the CWB will take all the Navigator that is produced under contract each

year. Navigator has one feature that is relatively unique among durums

at this time. It has a brighter yellow pigment in the seed and hence

produces brighter yellow pasta. There is a niche market for a small

amount of this durum, and Viterra limits production to this amount by

limiting the contracts it lets out.

Commander durum has less to commend it. Yields are fairly high relative

to other varieties, and like Navigator, Commander has stronger gluten

than other durums. However, Commander has the very undesirable habit of

accumulating cadmium in its seed. Cadmium is a toxic heavy metal that

has become a source of concern to consumers of durum. The CWB limits

contracts for Commander in certain parts of the prairies where cadmium

accumulation is especially problematic. Like Navigator, Commander also

limits what growers can do with their production. Many farmers don't see

the closed loop system as a desirable thing. There is some evidence to

indicate that farmers whose marketing options are restricted by

contracts receive lower trucking premiums and poorer grades when they

sell their grain.

Fortunately, those wanting to grow stronger gluten durum have an

alternative. Strongfield durum, developed by the same Agriculture Canada

scientists who developed Navigator and Commander, is a strong gluten

durum with superior milling qualities. It has better yields that

Navigator, and, with it being licensed to SeCan, farmers are able to

keep their own seed for replanting, and are not nearly so restricted in

marketing options.

The CWB has been anxious to get Strongfield into greater production (it

occupied 43% durum acres in Saskatchewan last year) in order to improve

the quality of the durum it sells. The CWB has also generally required

companies that want contracts for Strongfield to allow farmers to

replant their own seed.

Viterra's aggressive measures to protect its control over Navigator will

not sit well with many farmers. No one likes to think that the future of

grain production lies in closed loop contracts that limit a farmer's

access to both markets and farm supplies. The huge growth in Strongfield

acres indicates just that. Rumour has it that Viterra hasn't limited its

threats to farmers. Other grain companies have been told that they might

be held liable if they buy Navigator durum. At least one company

responded by saying that if Viterra allowed Navigator to contaminate its

elevators, Viterra would be held responsible.

(c) Paul Beingessner

Saskatchewan RMs Take a Beating From Transportation

Column # 668

Although it may seem as if the prairie branch line rail network has been

completely skeletonized by the major railways, the job is not yet truly

complete. CP still has 911 kilometres of track on its Three-Year Plan

for abandonment in the prairie provinces, and CN has 613 kilometres. Nor

does this rule out further abandonments by the major carriers. At least

one major railway has stated that there are still too many grain

elevator points and by extension, too many rail lines.

When the railways seek to abandon track, there is a formal process laid

out in the Canada Transportation Act. At one time, prior to the passage

of this act, the Transportation Agency had to take public interest into

account in deciding whether or not to allow an abandonment. That idea

was vanquished some time ago. The railways merely have to follow a

prescribed procedure, and cannot be prevented from abandoning track, no

matter what the government may think. It isn't exactly what the

country's founding fathers had in mind when they granted the original

railway charters.

The only defence of the public interest left in federal rail legislation

is the stipulation that a railway must offer a line for sale to various

levels of government before it can rip it out of the ground. Of course,

this wouldn't mean much if the railway could charge whatever price it

wanted. The rules say that the price will be the net salvage value of

the track - the amount of money the railway would get by selling the

materials less the cost of tearing out those materials. If the parties

can't agree on that amount, the Canadian Transportation Agency (CTA)

will decide.

Until recently, the Agency has been fairly reasonable in these

determinations. Neither party usually got what it wanted completely. But

two recent net salvage value determinations on Saskatchewan branch lines

seem to indicate the tide has turned in the railways' favour. The new

Members of the Agency, freshly appointed by the Harper government, gave

the railways a huge and questionable bonus in these recent rulings.

The bonus revolves around a section of the Canada Transportation Act

that requires the railways to pay to municipal governments, on

abandonment, an amount equal to $30,000 per mile, for each mile of rail

line that runs through the municipality. This provision only applies to

grain dependent branch lines in western Canada. The rationale for this

was to compensate municipalities for road costs they would incur when

rail service ended.

It would seem this condition imposes quite an obligation on the

railways. Prior to the recent run-up in commodity markets, including

steel, a railway would likely have ended up in a negative position when

it abandoned track. This makes it all the more odd that this provision

in the act was, if memory serves me correctly, first proposed by CP.

The fact is, CP was quite clever in suggesting it. Municipalities have

been fighting with each other ever since the act came into effect. While

one municipality may want to buy the track to operate a short line,

another will see only the short-term prospect of hundreds of thousands

of dollars of revenue.

Given this provision, it would seem logical that the net value of the

track would include consideration for the $30,000 a mile. It the railway

abandons the track, it can sell the materials but must take the payment

to municipalities out of that money. There is no way around this.

Salvaging the track includes a compensation cost to the municipalities.

At least that is what seems logical. Unfortunately for farmers on the

Radville and Bromhead branch lines, Harper's appointees to the Agency

don't appear to see it that way. If CP sells to the RM's in question, it

gets to have its cake and eat it too. The RMs pay the full price and

lose the benefit of $30,000 per mile. And if they want to start a short

line, they are still at the mercy of CP as to all and any conditions the

line would run under.

To top it off, the Agency also ruled against the RMs where their

reclamation bylaws were concerned. Having seen the condition of many

abandoned branch lines, some municipalities enacted bylaws requiring the

railways to clean up abandoned railway sites. The RMs in this case felt

the amount of such a clean up should be deducted from the salvage value.

Again the Agency ruled in CP's favour on this.

The resulting purchase prices for these branch lines are exceedingly

high. It is possible that the Agency's rulings might fit the letter of

the law as laid out in the act, but they violate any sense of natural

justice.

There is one last recourse in this case. The rulings can be appealed to

the federal court of Canada. A successful appeal would have implications

far beyond the two branch lines in question, and extend to the other

1300 kilometres on the railways' plans for discontinuance.

Given the cost of such an appeal, and the wide implications, the

government of Saskatchewan should consider funding it. For a province

swimming in oil money, it would be a small amount. For some beleaguered

RMs, it would be a godsend.

(c) Paul Beingessner

Although it may seem as if the prairie branch line rail network has been

completely skeletonized by the major railways, the job is not yet truly

complete. CP still has 911 kilometres of track on its Three-Year Plan

for abandonment in the prairie provinces, and CN has 613 kilometres. Nor

does this rule out further abandonments by the major carriers. At least

one major railway has stated that there are still too many grain

elevator points and by extension, too many rail lines.

When the railways seek to abandon track, there is a formal process laid

out in the Canada Transportation Act. At one time, prior to the passage

of this act, the Transportation Agency had to take public interest into

account in deciding whether or not to allow an abandonment. That idea

was vanquished some time ago. The railways merely have to follow a

prescribed procedure, and cannot be prevented from abandoning track, no

matter what the government may think. It isn't exactly what the

country's founding fathers had in mind when they granted the original

railway charters.

The only defence of the public interest left in federal rail legislation

is the stipulation that a railway must offer a line for sale to various

levels of government before it can rip it out of the ground. Of course,

this wouldn't mean much if the railway could charge whatever price it

wanted. The rules say that the price will be the net salvage value of

the track - the amount of money the railway would get by selling the

materials less the cost of tearing out those materials. If the parties

can't agree on that amount, the Canadian Transportation Agency (CTA)

will decide.

Until recently, the Agency has been fairly reasonable in these

determinations. Neither party usually got what it wanted completely. But

two recent net salvage value determinations on Saskatchewan branch lines

seem to indicate the tide has turned in the railways' favour. The new

Members of the Agency, freshly appointed by the Harper government, gave

the railways a huge and questionable bonus in these recent rulings.

The bonus revolves around a section of the Canada Transportation Act

that requires the railways to pay to municipal governments, on

abandonment, an amount equal to $30,000 per mile, for each mile of rail

line that runs through the municipality. This provision only applies to

grain dependent branch lines in western Canada. The rationale for this

was to compensate municipalities for road costs they would incur when

rail service ended.

It would seem this condition imposes quite an obligation on the

railways. Prior to the recent run-up in commodity markets, including

steel, a railway would likely have ended up in a negative position when

it abandoned track. This makes it all the more odd that this provision

in the act was, if memory serves me correctly, first proposed by CP.

The fact is, CP was quite clever in suggesting it. Municipalities have

been fighting with each other ever since the act came into effect. While

one municipality may want to buy the track to operate a short line,

another will see only the short-term prospect of hundreds of thousands

of dollars of revenue.

Given this provision, it would seem logical that the net value of the

track would include consideration for the $30,000 a mile. It the railway

abandons the track, it can sell the materials but must take the payment

to municipalities out of that money. There is no way around this.